Change is a universal constant. We can always rely on the truth that, no matter what we do, things change.

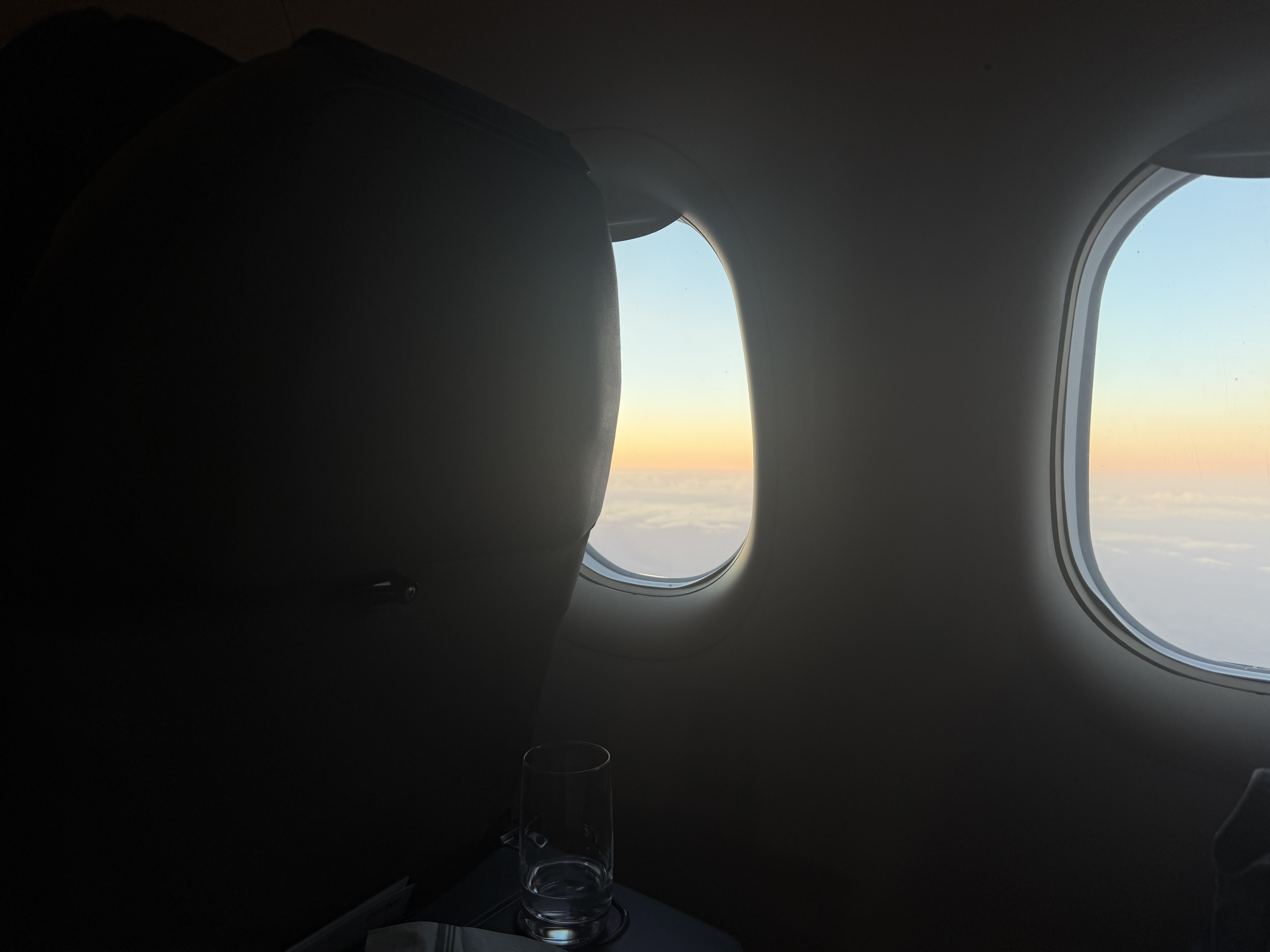

People, places, lives; these are all written in the language of impermanence, despite how tightly we tie ourselves to them.

Long before I could grasp the reality of “nothing lasts forever,” I had an obsession with Google Earth. It likely started with my dedication to the NORAD Santa tracker website that they ran every Christmas Eve. I thought it was so cool seeing that little animated sleigh travel the world. I felt comfort and joy (no pun intended), knowing that somehow he would eventually make it to my house. It might have been a total farce but it made kids feel special. I understood I was experiencing something I knew would transform into a memory. A memory I could return to when I wanted to relive that feeling of excitement, the irony of feeling unique in the same way every other child who believed in Santa and had access to a computer felt unique.

Both Google Earth and Street View became an outlet for me to explore the world from the comfort of my own home. I would look up my old schools and addresses. From there, I would soar to the Himalayas and summit Mount Everest on my homescreen. All these places that I could not go to physically; yet, there I was, in a sense, on a journey. It felt more real than an image search, or flipping through old photo albums. The globe aspect of it, the spinning and panning, made it feel like I was actually traveling somehow, that I was tracing my steps and marking my destinations as I flew from one location to the next.

In hindsight, my digital roaming was more than just play. It was, perhaps, an early experience with psychogeography. French theorist Guy Debord defined this concept through the practice of dérive, a kind of drifting where individuals move through space not with a fixed purpose, but with an openness to the emotional and psychological contours of their environment. Though Debord imagined this happening in city streets, I realize now that I was conducting a kind of digital dérive, swept up in the invisible currents of memory and meaning embedded in the virtual terrain. My movements were not aimless; they were led by nostalgia, longing, and a search for emotional anchors in pixelated places. I might have been walking on illusory terrains, but the feelings it evoked were genuine.

I forgot about my nomadic dérive with Google Earth and Street View for a while, only opening Google Maps to try and see if it was worth waiting for a bus rather than taking the tube. That is, until I came across an Instagram reel of a woman recounting a story of how a quick look on Maps brought her Dad back to life. She was looking at her parents house on Street View one day, and standing on the front porch was her late father, carefully watering his beloved plants, tending to the colorful flowers he loved to grow. The image was so mundane, typical, and unexpected that it felt like I was watching him in real time, like someone had just sent a picture of him that day from across the road. She said it was a beautiful surprise, a way in which her father stays alive and present in her life. It shows how even on a Geographic Browser, this modern online physical illusion, those we have lost still manage to meander back into our lives to say, “I might not be here, but look! Here I am!”

The comments were flooded with similar stories, and then my algorithm followed. There were all types of images: young friends and siblings mid-dance on a sidewalk unaware of their short lifespan, spouses that left abruptly with eyes full of adoration, beloved parents and grandparents laughing the day away, even pets carrying the same toys that they left behind when they had to go. All these lives full of love captured in a simple moment, existing in the precise ways their loved ones had known them to. Naturally, I was left in a puddle of my own tears.

These stories also took me down a rabbit hole of Google Maps/Earth in the hopes I might experience something similar. Desperate to obtain results in the way of Debord, I tried to find any remnants of my past life on the streets where I had once lived, in the homes of the family I’ve lost, as the giggly little girl I once was. I even tried to see if my late dog Frankie might be lounging on my back porch, his little golden body basking in the rays while maxing out his happiness meter as he did so well in the short ten years of his life.

For better or for worse, not every moment can be captured by a secret Google camera. I never quite found the people and creatures that had died and left me here in the present. But that’s the truth of it: you never fully do.

I knew that even if I had found my loved ones on Street View, it wouldn’t fill the void I wanted it to. Even so, I did get to see my old homes, and the homes of those I missed. In fact, unlike reality, Google lets you go back in time to see places as they were in specific months and years. Street View deepened my emotional connection to these spaces by placing me in specific moments in time, mapping out my past so that it could still exist in my future. That is the essence of dérive, to experience sentimental attachments to the physical spaces in the present. The fuel of experience and nostalgia allows us to better understand how the physical spaces that we inhabit throughout our lives define our identity and affect how we continue moving forward.

Through my own journey of dérive, I got to experience, from my current lens, those that shaped my youth and guided me to where I am now, despite their long absences. I saw their cars, their front lawns as they preferred keeping them, their backyard decor, and their sun lounging spots. Even without the image of my loved ones, witnessing snippets of time on Street View that, unlike most personal pictures, encapsulated the everyday aspect, meant the world to me. It’s like I have more evidence that these people, these memories, existed in our world, beyond the sphere of my individual experience. My knowing and longing for my past lives felt validated in a way I can’t quite say. Alas, that is the sound of mourning: inexplicable, yet begging to be expressed.

These digital maps, these everyday guides are spaces I take for granted. On the surface level, they tell me how to get where I aim to go. Yet, in reality, they are detailed and delicate collages of human existence. They tell the stories of our lives and ground us in reality, while allowing us the freedom to explore and escape. Even in the digital age, amidst the chaos of virtual maps and direct lines of travel, psychogeography is still relevant and possible. No matter what, memory and emotion play a large part in driving us towards our destinations.

It is much easier to figure out where you are going when you are able to remember where you’ve been. Wherever we are in the current moment, there will always be spaces in the present that open windows into the past. Those who came before us will always remind us that they were there.

People and places, despite their impermanence, continue to exist intangibly, in our memories, both real and virtual.

You never know, somewhere, somehow, your mom or your grandpa, or whoever it is that you miss, is out there. They might still be tending to their garden, or dancing on a sidewalk, forever digitised in a moment of everyday bliss to remind you that who they were is who they will always be. Past, present, and future.