“Not compatible how?” Face to face, side reclining between blush sheets that match the shade of the headboard, the same hue bathing the walls and ceiling, naked physically and emotionally, we softly consider this question.

“Mmm,” he utters, hesitantly. “You’re always taking so many pictures. I don’t need to take photos. Or at least not so much. I prefer to be present.”

Prefers? Needs?

For someone who has chased and relished adventures, flimsy and extraordinary, at home and abroad, over five-plus decades, the inference that I have not lived a life fully present struck a nerve. He also wasn’t the first to raise my compulsion to take photos. Just ask my ex-husbands, my teen daughter, my sprawling matrix of friends and colleagues.

I understood why my lover, with 31 years between us, might make this leap. His generation, the alphabetically penultimate “Z,” were the lab mice of the first wave of smart phones. They have not known a world without a device in hand. A device that fills wants humanity didn’t even know it had. Provides data we once could live without. Snapping whatever like an itch we no longer know why we’re scratching.

The results are sometimes of value. But most are expendable, cluttering smartphones and data clouds because users can. In another time, some of these images would remain private. But the validation of a “like” is habit forming. The impulse mostly discounts composition and other artful elements, let alone intention, all of which require a conscious attention. And this at a time when the existential realities threatening our world are in dire need of our individual and collective focus. To be fair, Relentless Photo Taking runs across generations. It’s a dopamine hit we collectively can’t quit.

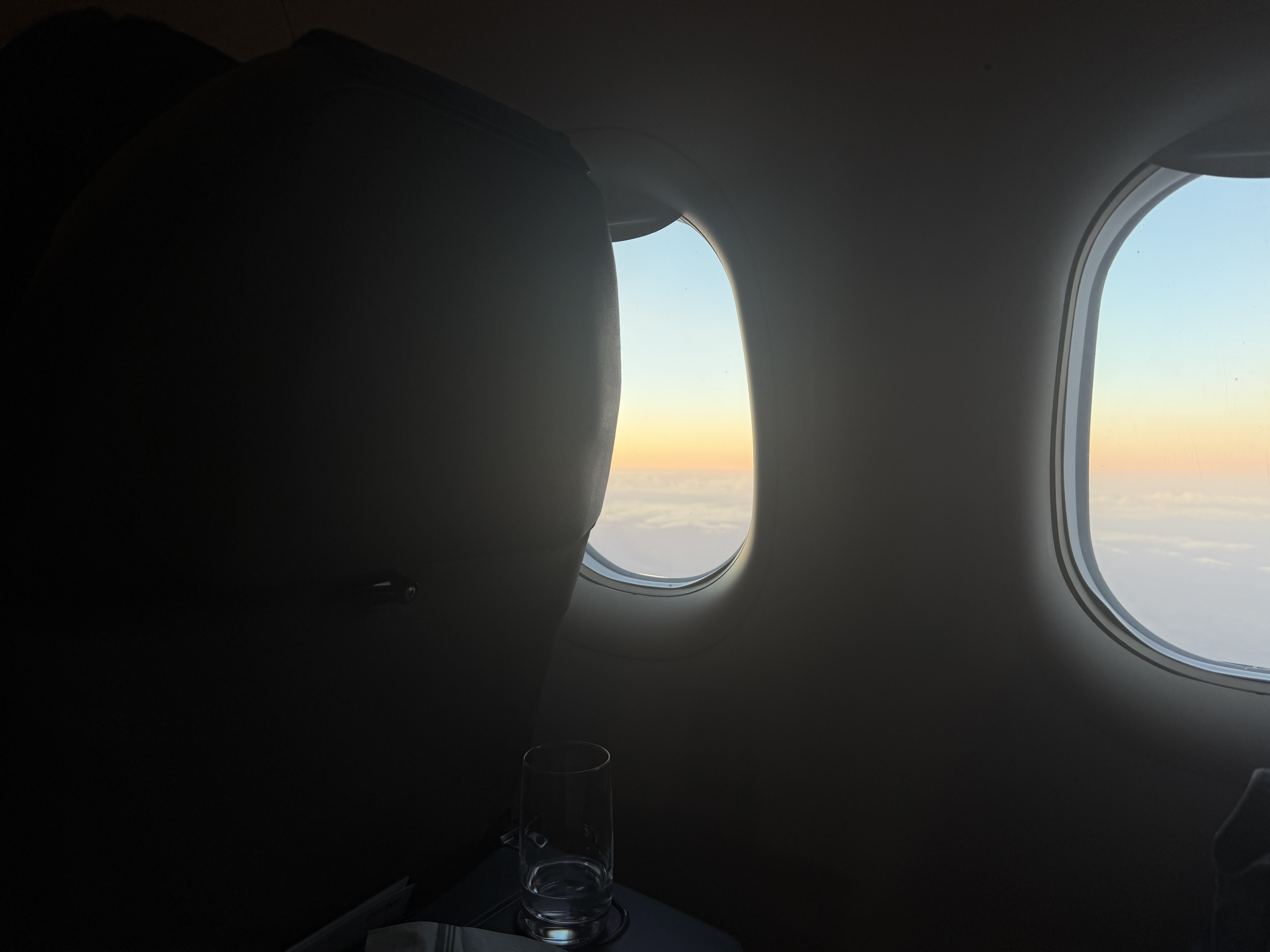

I was ordering my second caipirinha, at a bar with an audacious view of the Pacific. The grounds were part of a private, blinding-white mid-century home. I was there on the invitation of one of the five women celebrating a birthday. The modern art by all the usual suspects, the Pacific Palisades zip code, all of it couldn’t absolve the hosts, a tech bro and his high-priced wife, or their guests. As I kept watch on the bartender muddling the sugar, a breathy, red-blooded voice cut through the sunset-hour electronica. “I know your game. I know what you’re up to with that camera.”

The truth stings. In this case, it stung me right into momentary paralysis. I recast my gaze from the bartender to the source of this incrimination. It’s the party photographer, swarthy and sinewy from surfing, which this native Brazilian shared earlier he indulged in all his life. We’d been taunting one another since I arrived, jockeying for the same shots of the birthday squad. I got mine quickly, as always, with my digital camera or iPhone. Languidly, flirtatiously, he cajoled the women to mug for him for a second or fourth pose.

“I know exactly why you do that,” he insists, breaking my spell, his aqua-colored eyes penetrating me. He points to the Sony RX100 I’m clutching in my right hand. My other hand grips the lime-scented drink tighter.

“There is you,” he says, gesturing in prayer at an angle.

The prayer hands then shift to the other side. “And there is everything else. Your camera allows you to venture into whatever space you want. It is a shield. It is protection. You can talk or not. You can be among these people and be with them. Or you can pretend to be with them by holding up your camera. But you are not really with them. This is what you do. You are here. But on your terms.”

A shield. Protection.

His impressions struck a nerve. I rather enjoy a confrontation, especially a well-meaning one. But he was on to something. That someone else recognized this proclivity was as unsettling as it was thrilling. I wanted to keep listening to him deconstruct my M.O. But we both had more photographs to take before the sun dipped out of sight.

I will add here that no one who has spent time with me would mistake me for an introvert. I’m the first to raise a toast at a dinner party. I relish speaking to a conference room filled with a thousand strangers. I also have little tolerance for banal conversation. I want to go deep—when the individual and situation warrant it. Otherwise, I’d rather let the lens get me through the moment.

I also know that everyone, even those who insist differently, likes to be recognized with a photo op. More often than sharing trivia about themselves. So, after a bit of expeditious small talk, I snap and sail. I’m at the other side of the sea of revelers before the inevitably awkward, invariably tedious moments creep in.

It's not all about keeping myself at an entertained distance from everyone.

The eye has to travel, Diana Vreeland proclaimed. My eyes are collecting air miles like a shiny new flight attendant. According to the fashion doyenne’s gospel, the eye moves from reality to the imagination in the interest of personal and creative growth. One cannot move forward, creatively and in other ways, without rousing the senses, and that starts with visual stimulation.

Whether I’m selecting photographs for a cover, shooting for myself or others, or adding to the collection crowding my walls, photography is a journey this nomad and her camera will forever carry on. The camera lens facilitates a focus that heightens perception in the momentary “now.” The prosaic can become precious. The ephemeral presence of mind and stimulation, the documenting for future memory, precious, too.

Prioritizing the visual is what concerns scientists researching the effects of smartphone cameras on memory. Studies conducted at a swath of blue-chip universities have found that smartphone cameras alter how we process the world. Our focus on visuals also focuses our attention, enhancing memory. But not fully. Surrounding stimuli—specifically sounds, smells—may be ignored in the process. Smartphone cameras compromise the whole experience.

I beg to differ. Maybe that’s because I approach taking photographs as a writer: the textures and smells, the taste (not always, but I might consider the saltiness of skin), the song or silence soundtracking it all. I want the full cinematic experience. A camera lens grounds me. In the sensory explosion that is life, a camera helps me establish place, physically and psychologically. It provides a framework, literally, for processing what I am witness to. It gives substance. Past or present or even future, the pictures as much as taking them convey I am here.

I click, therefore I am.

I explain this as succinctly as possible to my lover. “That is you and I am not saying there is anything wrong with that. But I better understand your reasons now,” he says, as he draws me in with his sculpted arms, the hairs of his chest pleasingly grazing my nose.

Now 10 months since our pillow talk, his uneasiness about my photo-snapping habit seems a moot point, and an amusing one at that: when we’re out or in a more intimate space, he is one of my most willing subjects.