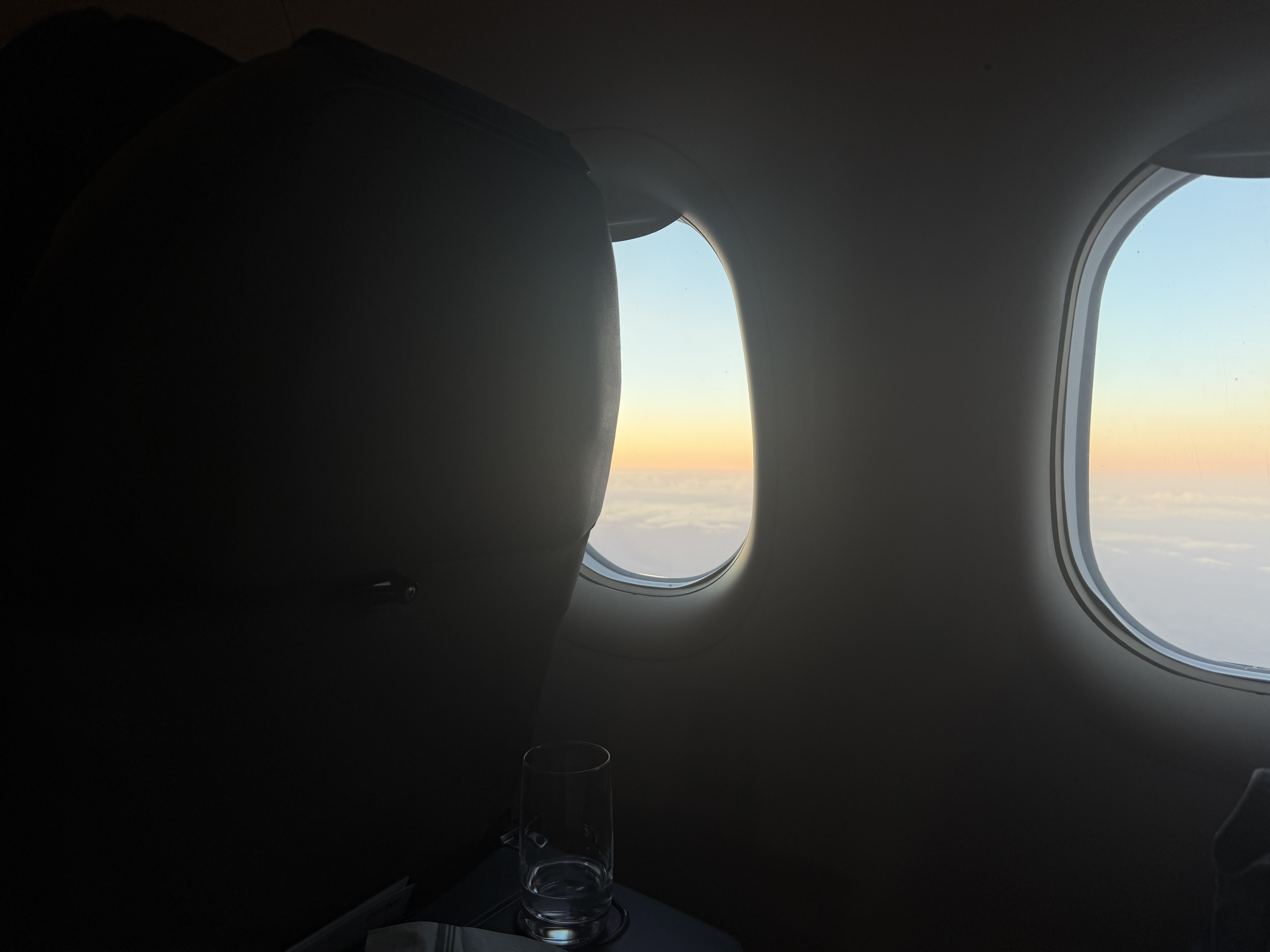

The high pitched ring of granddad’s hearing aid echoed in my ear and the sweet smell of grandmother’s hairspray filled my nose as I jumped into their arms. I closed my eyes and soaked in their soft, loving greetings in that familiar southern inflection, breathing in the humid air of Mississippi. I could already taste the ceremonial corndogs, the first meal at the house on Jiggetts Road that always marked the start of vacation, of two weeks off from school back home in Paris. A brightness shimmered, my body coming alive no matter how groggy after the long flight. My senses were drinking in the whole experience.

I did not know it then, but this was a window into the nature of presence, into the visceral feeling of inhabiting ourselves fully. As a young child in that airport, held softly by my grandparents, my body opened into a deep intimacy and connection with the moment.

Presence was natural back then, as uncomplicated and direct as the feeling of my limbs. Somehow its memory was left behind, as my body and I began to come apart.

It was a slow, subtle unweaving. A little before my ninth birthday, I saw how bodies could kill, how they could eat themselves from the inside and turn you to ashes like cancer did to my father. The spontaneous activity of my body became a threat to monitor. I was afraid of uninvited aches and pains, of the subtle vibrations in my limbs, of my own heartbeat. In the space where my body used to be, a claustrophobic tension crept in, a latent drone of emotional heat that made it feel like I was wearing a suit too tight, constricting and shrinking the scope of my life. I moved upstairs into the attic of my mind, camping out in the realm of imagination and distraction. It was a natural refuge: I had learned to engage with the world through the prism of the thinking mind. I knew that it was always on and available, plugging the gaps in understanding, a temporary reprieve from the stirrings in my flesh.

The world around me felt designed to keep me up there, locked away. Hypnotised by the blue light, earphones embedded in my skull, I feel the partitioning of my attention begin, pulling me out of myself and into an unsolvable algorithmic labyrinth. At the mercy of this ecosystem, I am tossed around like driftwood in the churning sea of content. Our culture funnels our focus upwards, overwhelming our eyes and bombarding our ears with constant information. Tunnel vision and saturation ensue, equivalent to sensory deprivation. As the ubiquity of screens in both our work and leisure mediates how we interact with the world, we are separated from our direct experience.

Our existence becomes increasingly vicarious, attention yielded to influencers and parasocial relationships with our favourite podcasters as we withdraw seamlessly into worlds inhabited by digital others. When escapism becomes the norm, we are launched into orbit around ourselves.

We become uprooted, fallen trees severed from the fabric of the forest. Not fully here, a sense of disembodiment rippling outwards and reflected in how we consider others in the social body.

Escape hatches only took me so far. No matter how much distance I tried to put between us, my body could not be ignored, playing its dissonant music louder the more I pushed it down. Living as this floating head left me exhausted and unmoored. I was 24 and desperate for some peace of mind when I found myself on a regional train in the middle of France, on my way to a mindfulness seminar. As I arrived at the retreat center, I was intimidated by the stillness that echoed with the falling away of time. The space that emerged bumped up against my estranged fragments of self as I sat for hours in the main hall, hoping that, finally, something would give. It happened on the last day, and not in the way I had imagined, not in the way I had hoped. There was no stream of light, no blissful rapture, no transcendence. It was a simple prompt: we had 15 minutes to write a thank you note to our bodies. My words tentatively filled the page, wobbly and uncertain. But just as I wondered if they would be heard, we made contact. Each “thank you” released a memory of a beloved face, of a sweet taste, of a favourite song, reminding me that my body and I were inseparable. I had forgotten that it was the vessel through which I took in the world. That without my body, there would be nothing. No pain, but also no joy.

In my disconnection, I lost touch with an essential process shaping my every moment—the alchemical arising of experience. Raw inputs from the world flow into our ears, nose, eyes, mouth, and pores, blossoming out from our bodies into the proof of our aliveness. This is the realm of presence: a direct, unmediated sensory experience of being where we are. Our senses are porous and as we attune to them we become sponges, taking in all that is presented to us and squeezing out the excess, what does not belong, what has run its course. The boundary between us and the world falls away, revealing a profound connection and intimacy. In our disembodied states, we are left cold, isolated, siloed. We lose touch with the connective tissue of the senses, effaced by the relentless pressure of self-creation and progress our culture imposes upon us, that we impose upon ourselves.

The feeling of dissociation moulted and took on new names in the years that followed the reconnection at the retreat. It opened into layers of fear, shades of guilt, and nooks of self-pity. The sticky grief of an eight year old was dislodged and began to move as my body and I cried together, pooling at my feet and watering the sunflowers I laid on the marble floor beneath my father’s urn.

I understand now why I disconnected. We disconnect from our bodies because presence can be uncomfortable, its raw, visceral nature stripping us down to our most vulnerable. The fact of its boundlessness lays us bare, undefended, here in the midst of it all. That is the price of the return ticket back into our bodies, into our roots—we are brought face to face with the intractable knots, the calcified cadences of a forgotten inner life begging for release. It may not feel peaceful, but it forces us to make peace, our senses confronting us directly with the most unsettling aspects of ourselves and our world, with the inherent unpredictability and insecurity of existence.

Yielding to the discomfort, we may find a path into the depths that lie below curated existences and manufactured emotions, into the tangible reality of experience.

There, if we listen, might we hear the body’s call, reaching out, inviting us back home to a warm stillness where for a moment we can allow ourselves to become whole again. For is there not a feeling of openness, of expansion, in moments of real presence? In deep conversation with a dear friend, time and space merge to make room for the fizzing elements of the creative chemistry that births experience. A primal sense of being here, at that moment, welcomes into existence the rhythm of the words, the light of the sun, and the sound of the wind playing in the leaves.

I pull my suitcase next to me and adjust my shoe laces. Looking out past the ramp leading to the exit, I see them in their familiar position. Granddad stands and waves, with grandmother next to him on her little scooter to ease the pressure on her feet. Slower, the exuberance of childhood having worn off, I walk out onto the bright tiles of the concourse. Too big to jump into their arms, the embrace is more steady now, deliberate. I am flooded with the familiar aliveness, and this time I watch as the world falls away in the intimacy of the moment. A memory left behind flourishes again, and I never want to forget.