A Little Misery: How suffering is fetishised in our popular culture

Death, taxes, and suffering. We wake up in the morning and take stock of our physical state. The little niggles, remnants of a slowly passing cold, or the grind of something more chronic, the push and pull of personal pain, a pain grinding you down over months, years even.

Everyone suffers, so it’s an expectation, perhaps a duty, of art to address and reflect on our darkest moments, the kink of the human condition which splinters our sense of self and makes us wonder if simply being alive is even worth the effort.

Still, there remain important questions surrounding the use of suffering in writing.

Can we trust authors to treat suffering with dignity, respect, and compassion?

Is it possible for authors to forget these responsibilities - to treat suffering as a point of intrigue and drama, to become a voyeur of their characters’ misery, perhaps even to make it into something of a fetish?

Do you know Jude?

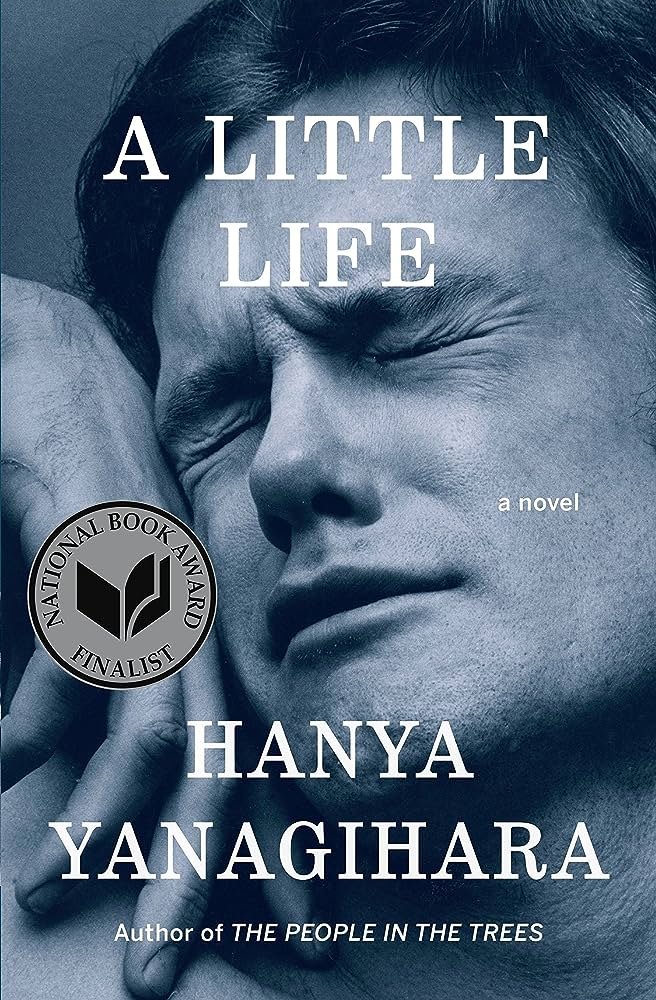

A Little Life, Hanya Yanagihara’s literary explosion, is a novel of obsession, specifically an obsession of Yanagihara with her own protagonist.

She invented Jude’s chronic self harming, his vomit inducing rushes of spinal agony, his minimal, almost non-existent sense of self worth. For a character fleshed out over 700 odd pages of high quality prose, Jude is something of a flat character.

He is predictable and linear, like Batman or Superman, if they were also afflicted with an opaque disability; But that’s not the only superhero quality of Yanagihara’s central character.

Jude is a kind of intellectual hero, amongst the highest of achievers.

He has an exceptional legal mind, becoming a top class solicitor, as well as being an appreciator of literature and art, and, oh yeah, he’s also an incredible baker, rustling up a plate of amoeba shaped cookies for the biologist wife of his legal mentor and future adoptive father.

If this all sounds a little overblown, it is because it absolutely is. Jude can’t simply be a normal man who suffers, he has to be an exceptional man, who suffers exceptionally badly. His talented legal mind, powerful intellect, and flawless ability to analyse the world around him, doesn’t seem to bring Jude much pride at all.

When he wins court cases, crafts delicacies, and mops up difficult texts, Yanagihara treats us with the same voice as the ones describing his suicidal tendencies, bouts of self harm, and flash backs to childhood sexual abuse.

We are left wondering, what does Jude’s suffering actually mean?

Stoic PursuitsA key change to the way we view suffering is taking place in our culture.

Stoicism, a philosophical belief in personal endurance in the face of suffering, is experiencing a revival.

Thinking that suffering is some kind of test, a challenge of the universe, has been replaced in the modern doctrine of Stoicism by a way of thinking that views pain as a meaningless beast that can be muzzled by lifestyle changes, mental training, and leaps of mindset.

Now, rather than being some kind of test set by a higher power, the keys to a better way of living are shown to be within us. The champions of Stoicism would find Jude to be a perfect target for their way of thinking. Yanagihara constructs Jude as a constant victim, consumed by his own suffering. Throughout A Little Life it is implied that Jude’s pain makes his misery inevitable. The New Stoics would consider Jude as someone lacking in discipline, in need of strong personal walls to stand up to his rotten lot in life. The current Stoic revolution in thinking is headed by a latter day prophet, but rather than a dusty old man with a beard and robe, this spiritual leader has icy blue eyes, slick black hair, an impeccable jawline, and total command over the internet.

The man in question is Ryan Holiday, a marketer turned bestselling philosopher and author.

Like all the best public intellectuals, Holiday took to Joe Rogan’s podcast to discuss his philosophy, and animated, wide eyed, and handsome, he cut the figure of a true celebrity philosopher.

‘If I tell you to describe a philosopher, you’d think of a university professor, turtleneck, like, tweed... you’d think of a weakling.’ He says.

A weakling, Ryan Holiday is not...

‘Ancient philosophers did shit [...] and what I love about the early Stoic philosophers is their metaphors are all sports... it’s wrestling, and fighting, and running, and hunting... because they did those things.’

Joe Rogan pitches in:

‘And difficult things... are good for you... and they’re good for your mind... that’s what people [who don’t pursue them] don’t understand.’

Jude, what do you make of this?

Whilst you study law, bake, maintain your circle of artistic friends, and cultivate your intellect, do you also make time for hunting, fighting, and running marathons?

Have you considered, maybe, that these lifestyle changes could go some way in curing your life of suffering?

Whilst it is easy to criticise Yanagihara for her excessive helpings of misery, I think Jude fulfils a realistic image of how some people view their own suffering.

During my own forays into depression and chronic pain, I have also overlooked my achievements in favour of helplessness and self pity. It often seemed as though the mainstream had little answer to my woes. Having worked in a couple of bookshops, I came to notice certain characteristics of the self help books on display.

These books, by their very definition, have an extreme focus on ‘doing.’ They tell you to wake up earlier, journal your thoughts, note the things you are grateful for, clean your living space, work out, bake, do team sports, and breathe - for God’s sake, remember to breathe!

In doing this write up I tried to figure out just what it was about these self-help books that leaves me cold. It soon came to me that one thing that is lacking in the self-help department is a focus on compassion - both in receiving and giving. A core tenet of Stoicism, for example, is introspective independence - the idea that the key to defeating one's demons comes from within.

Ryan Holiday, in an eye opening interview with the website Killing Buddha, reflected on his own complicated relationship with compassion and empathy.

‘I grew up as a very independent kid [...] when you’re in that situation it’s very hard to be empathetic.’ He says.

Holiday goes on:

‘Therapy and my writing have been about developing that capacity [for empathy]. I’m never going to be as good at it as someone who grew up that way.’

This moment of introspection from Holiday gives us an insight into the mind of the man, as well as the movement he is part of.

For Holiday, writing has been a process of learning empathy, rather than empathy being a starting point of his writing. We have to wonder, do the modern day thinkers on suffering actually know what it is to suffer? Or is suffering merely a focal point for a certain way of thinking - a fetish for writers who happen to be luckier than the people they claim to be helping?

A Little LightReturning to Jude, we can see Yanahigara’s own tense relationship with compassion. Jude is often depicted as a self-contained and sometimes spiteful character. One of his best friends, JB, a talented artist, paints portraits of Jude, and our main character reacts with anger and distrust. When Jude is adopted by Harold, the only true father figure in his life, he fixates on how he will destroy the relationship and ruin everything for himself.

Even Jude’s doctor, Andy, who inexplicably gives Jude endless free medical care, is treated with antagonism, the two constantly arguing throughout the narrative. Jude’s constant anger and rejection of compassion is one flaw that pokes through his flat character. Whilst Yanagihara has a right to explore the inevitability of suffering, she chooses to have Jude reject human connection at every turn. If compassion is one of life’s saving graces, even in the face of terrible suffering, Yanagihara makes Jude, at least partly, complicit in his own downfall.

I’ll finish with another masterclass in human misery, Isao Takahata’s masterpiece anime film Grave Of The Fireflies.

Fireflies focal characters, the young children Setsuko and Seita, are forced to watch their community burn to the ground during one of the worst crimes against humanity of all time - the Tokyo Firebombings of World War II, in which over 100,000 Japanese civilians were murdered by the US Air Force. The film has barely started as Setsuko and Seita stand over the bandaged, dying, body of their mother. The two children are sent into a spiral, being bullied by starving family members in the countryside before being exiled altogether.

Ultimately they both starve to death. If A Little Life can be seen as bleak, few narratives can be counted more depressing than Grave Of The Fireflies. And yet the movie is, I think, a work of true beauty.

Despite the most hopeless of circumstances, Seita never stops trying to make his little sister laugh, never stops trying to reassure her, never stops showing her humanity in a truly dark world. The best example of Fireflies’ outrageous hope comes when Seita and Setsuko are sheltering in a cave, and Seita collects a swarm of fireflies in a jar.

When night falls, he releases the insects into the darkness of the cave and an ethereal explosion of light illuminates the enchanted faces of the downtrodden children.

The next morning Setsuko wakes up to see that the fireflies have died. She is upset, confronted by the fragility of beauty in nature, by the inevitable march of mortality.

In a way this foreshadows her own fate. But whilst Fireflies potent depictions of human suffering make a lasting impression, it is the haunting vision of wonder in the cave which lasts longest in the mind.

Even in the bleakest of moments, the audience is shown hope, even in isolation, we see that simple acts of compassion can exist.

I’ll be honest, I didn’t finish A Little Life.

I was already worn out by Yanagihara’s miserable vision when my copy was reduced to a sodden, unreadable, mess by a rainstorm on the ground of a music festival campsite. I realised that I didn’t have a desire to finish the book.

There was always something voyeuristic about Yanagihara’s vision of Jude, something I found uncomfortable.

I can take Yanagihara, able bodied, writing a disabled character, I can even take Yanagihara, straight, writing a gay character who experiencing male-on-male sexual violence, but what I couldn’t take was the misery with which the author played Jude’s misfortune. In my opinion, Jude was always Yanagihara’s sexualised, suffering, misery fetish.

It is little wonder the book was so successful, given the hunger for flat depictions of misery.

Just as Yanagihara offers a view of suffering which could be seen as manipulative and lacking in humane understanding, The New Stoics offer a similarly incompassionate take. What both lack is an empathy based in hope. The feeling that humanity can exist for its own sake, and through this we find life something worth living.

Whether gawping at Jude’s physical and mental decay, marvelling at gruesome murders on true crime shows, or scoffing at relationship breakdowns on reality TV, there has never been more options for spectating the misery of others.

But, maybe, there is still room for hope in literature and art in general.

Now that my copy of A Little Life resembles a discarded tea bag, I resume the hunt for my next good read.

I just hope it will show me A Little Light.Image credits: Inside Wrestling June, 1980, Breathe issue 45, Pablo Picasso, The Old Guitarist, 1903